Wake Up Dead Man Review: A Knives Out Mystery – A Quieter Kind of Clever

A stripped-back, darker Knives Out entry that deepens Benoit Blanc and lets Josh O’Connor quietly steal the show. Here’s our Wake Up Dead Man review, verdict, pros, cons, and what lingers after the credits.

Rian Johnson pares back the spectacle for a smaller, darker whodunit that finds new depth in Benoit Blanc and lets Josh O’Connor quietly steal the show. Now streaming on Netflix.

A mystery that does not rush to impress

The Knives Out films have never been shy about their cleverness. Accents are leaned into. Twists are announced, then inverted. Social satire is worn loudly. Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery still enjoys the mechanics of a good puzzle, but it feels noticeably less interested in performing them. Instead, it slows things down, tightens its focus, and allows the mystery to sit in a stranger, heavier space.

This time, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) is handed what the film openly frames as a “perfectly impossible” crime, the sort of whodunit he openly delights in. The pleasure of watching him circle a puzzle like this remains intact, but what stands out in this Wake Up Dead Man review is how much room the film now gives him as a character. Beneath the snappy dressing and theatrical drawl, Blanc is beginning to show the weight of experience.

A closed community and a perfect impossibility

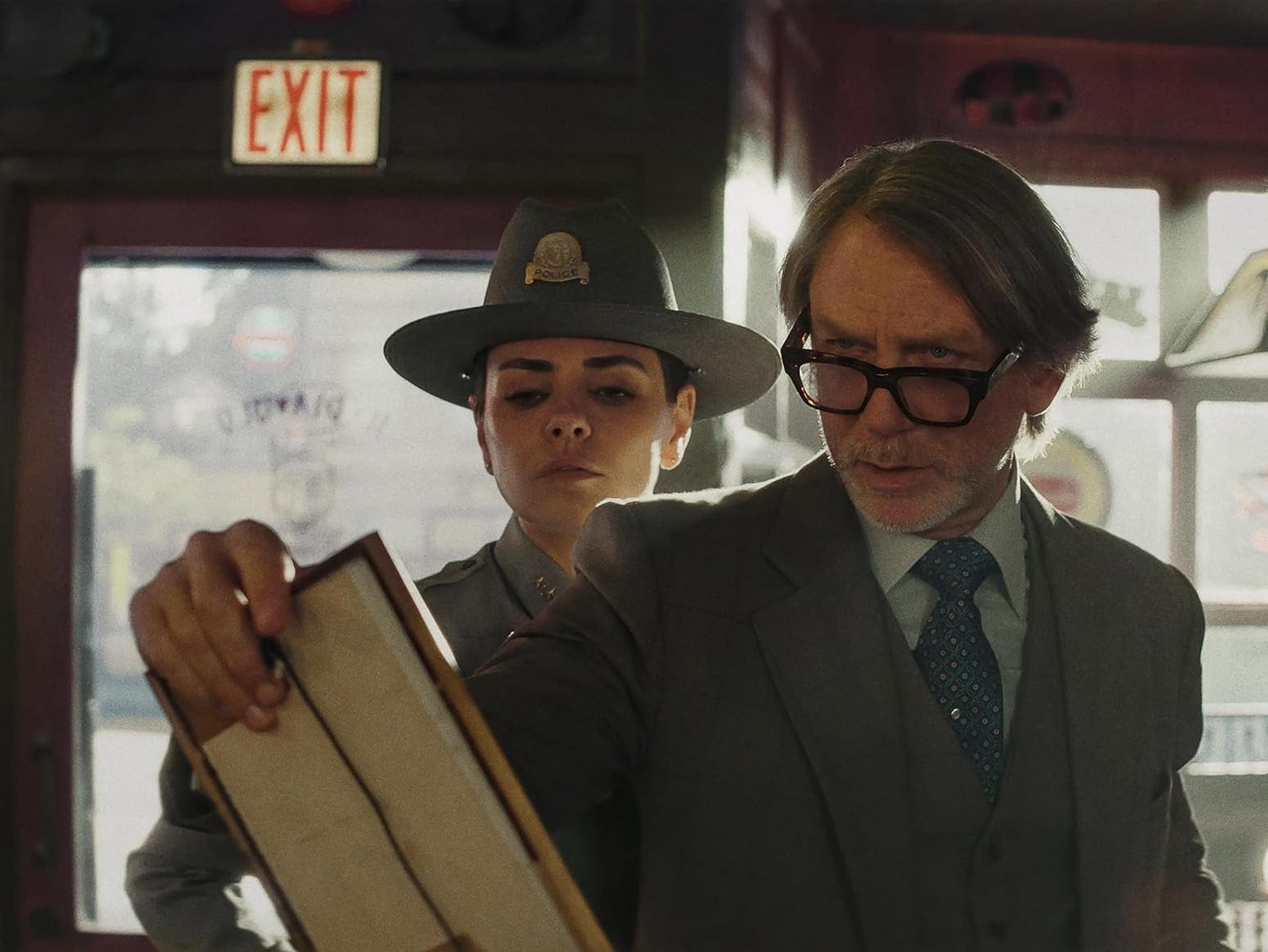

The mystery centres on a murder at a struggling rural church in upstate New York, a place held together by habit, loyalty, and a shared reluctance to look too closely at itself. Blanc arrives to untangle what happened, only to find himself working closely with Father Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor), a former boxer turned junior pastor whose patience and kindness immediately set him apart.

Jud is also, inconveniently, the prime suspect in the investigation into the death of the church’s fire-and-brimstone head priest, Monsignor Jefferson Wick (Josh Brolin). From there, the case folds in on itself, not just as a puzzle to be solved, but as a test of belief, power, and the stories people tell themselves to live with what they already know.

Faith in the attention economy

The setting does much of the work. This is a small town orbiting a declining church, where numbers are down and influence is shrinking. That scarcity sharpens everything.

Father Wick presides over this world with a confidence that edges into something more possessive. His flock has narrowed. Newcomers are prized. Reaction matters more than reach. Belief, in this context, feels curated rather than shared.

The film quietly reinforces this through a younger congregant (Daryl McCormack), who is rarely without his iPhone, filming and uploading sermons online. Clips are packaged for visibility, trimmed for impact. Faith becomes content simply because that is how attention works now, less about reflection than about being seen. The film does not moralise this shift. It simply observes it, which makes it more unsettling.

Father Jud and the case for grace

Set against Wick’s need for control is Father Jud (Josh O’Connor), and the difference registers immediately. O’Connor plays him with an unforced warmth, attentive rather than charismatic, the kind of presence that draws people in without asking for anything back. His scenes with Blanc settle into the film as a quiet centre of gravity, less about extraction than exchange.

Jud’s instinct is to slow things down. While on the phone trying to tease out information that might help the case, the call wanders. The person on the other end begins talking about her own troubles, and Jud lets the investigation recede. He listens. He stays with it. The urgency dissolves, replaced by something more human. It is not framed as a grand moral act, just a reflex, and that is precisely the point.

Later, Jud names this impulse as “the road to Damascus,” not as a dramatic conversion, but as a reminder that change rarely comes from being cornered. In the biblical sense, the road to Damascus is about sudden revelation, but here it is gentler, almost mundane. People are moved not by exposure or pressure, but by being met where they are. Guilt needs grace, not spectacle.

When Jud talks about faith as storytelling, as something people reach for to make life livable, the idea lands without ceremony. It reframes the mystery, but also reframes Blanc’s role within it. For once, the detective does not dominate the room. He listens. He absorbs. The film allows this philosophy to seep outward, quietly shaping its rhythm and its sympathies, without ever insisting that it has solved anything beyond the crime itself.

Benoit Blanc, still paying attention

What’s striking this time is not a reinvention of Benoit Blanc, but a loosening. Across the franchise, Daniel Craig has gradually pared the character back, and here Blanc feels more at ease in his own skin. The accent, the flourish, the pleasure he takes in an impossible puzzle are all still very much intact, but they no longer dominate every scene. Blanc remains openly agnostic, curious rather than sceptical, content to observe as much as he deduces.

That shift plays out most clearly in his scenes with Father Jud. Blanc never approaches him as a suspect to be dismantled or a belief system to be challenged. Instead, there’s an easy chemistry between them, a genuine back-and-forth that feels closer to conversation than interrogation. Blanc doesn’t share Jud’s faith, but he’s open to the way Jud moves through the world, the patience, the willingness to sit with people rather than extract from them. Over time, it’s clear he comes to care for Jud, not sentimentally, but attentively. The film doesn’t suggest that Blanc abandons his scepticism, only that he’s willing to make room for another way of seeing, and that subtle adjustment gives this entry much of its warmth.

A disciplined ensemble and dry humour

The supporting cast is predictably starry and refreshingly restrained. Glenn Close glides through her scenes with effortless authority. Andrew Scott has limited material, but handles it with precision and restraint. Nobody strains for attention.

Even the humour is handled lightly. Father Wick’s so-called confessionals to Father Jud are quietly hilarious, pockets of self-importance delivered with just enough sincerity to tip into absurdity. These moments of levity are scattered sparingly, and they land because they are not trying to steal the scene.

Less spectacle, more aftertaste

Rian Johnson paces the film with confidence. Clues surface gradually. Revelations arrive without fuss. There is no sense of the film racing to out-clever itself or its audience.

Compared to Glass Onion, which leaned hard into spectacle and satire, Wake Up Dead Man is smaller, darker, and more inward-looking. Less eager to impress. More interested in atmosphere and consequence. What lingers is not the solution, but the discomfort around it. The sense that truth, once revealed, does not automatically repair the damage belief systems can cause once they harden.

In choosing restraint over escalation, Wake Up Dead Man clarifies what this franchise does best when it trusts itself. Not just puzzles, but people. Not just answers, but the uneasy quiet that follows them.

Quick FAQ

Is Wake Up Dead Man worth watching?

If you want a louder, shinier sequel to Glass Onion, this may feel restrained. If you want a smarter, moodier mystery that lingers, it absolutely lands.

Is it funnier than the last one?

Not really. The humour is drier and rarer, which makes the best bits hit harder, but there are fewer of them.

Does Benoit Blanc feel different here?

Yes, in a subtle way. He’s still Blanc, just less performative, more observant. The film lets him listen.

Optional add-ons (not rewriting, just helpful)

- Featured image alt text: “

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest updates and news

Member discussion